Glimpsing North Korea: The DMZ

In July, my friend and I finally undertook a destination I’d wanted to go for years: the Korean DMZ. The DMZ is the DeMilitarized Zone, the border between North and South Korea, the 38th parallel. There lies many observatories, museums and even a cable car, along with the legacy of a brutal war and the mythologizing that came after.

It’s a big tourist site for foreigners and Koreans alike, with some tours offering sights of the JSA (the blue buildings you probably have seen in pictures) and the distant blue mountains of North Korea.

Some people I know have mixed thoughts about treating the DMZ as a tourist spot. Everywhere we go, we should be mindful of how our money and presence affects the places we visit. I strongly believe that visiting North Korea as a tourist is unethical, since you’re quite literally giving money to an oppressive regime and treating the North Korean people as an exhibit, an attraction. This is a controversial opinion, but one I believe strongly. I think there’s no excuse to visit North Korea as a civilian.

But is visiting the DMZ ethical?

Let’s examine that.

Buuut first, I’ll give you a rundown of how my friend and I visited.

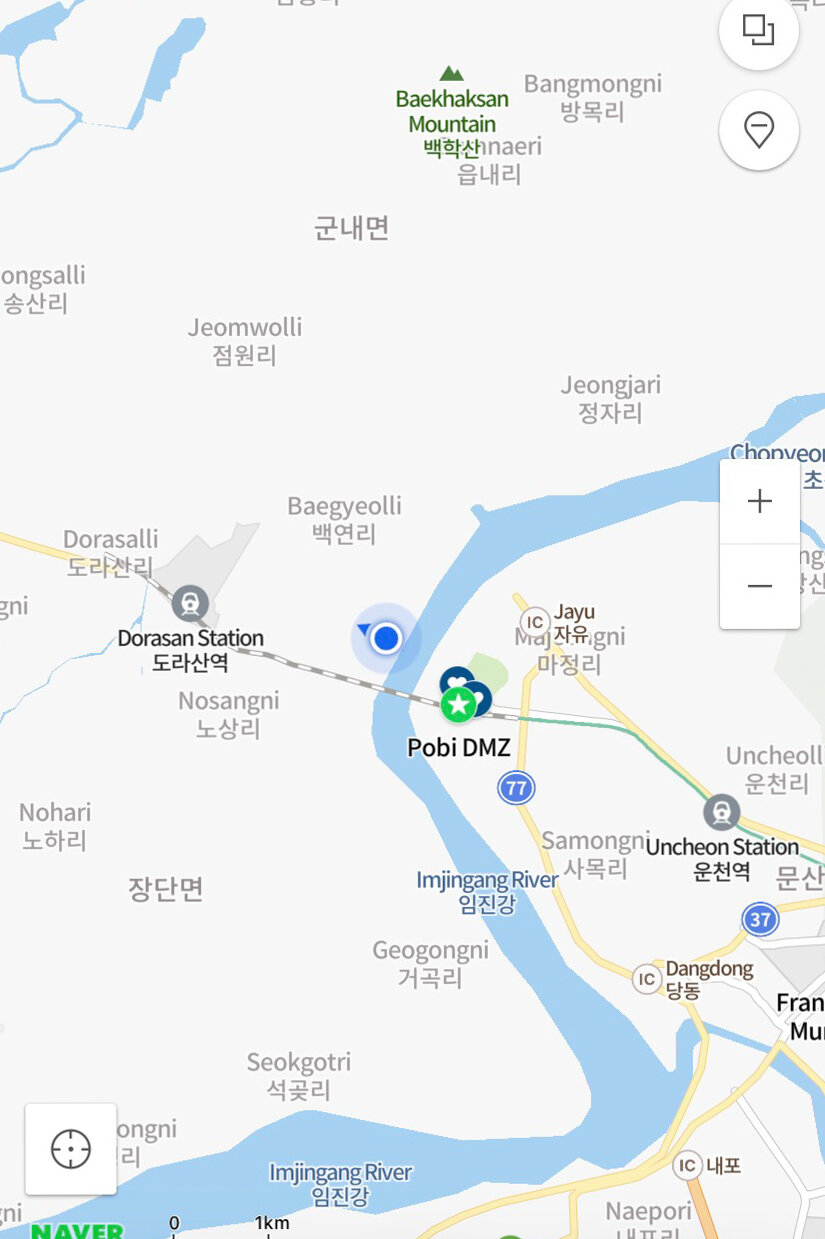

You can visit the DMZ without a tour. In fact, given COVID, most are closed. So one early morning, we took the Gyeogui-Jungang line from Seoul for about an hour. It’s a subway train so you sit parallel to the tracks, watching the high rise apartments grow fewer and fewer the more north you get. This is Gyeonggi-do, the large and populated area around Seoul.

After we arrived at Munsan Station, we took a cab (busses were few and far between) to Paju station, which was only about 10-15 mins away.

When we arrived, it was already HOT. I’m from Texas, I’m warm-blooded and I’m no stranger to heat, but…y’all, Korean summers are something else. It was muggy and the only thing that kept me from losing it was the frozen watermelon drink I got from GS25.

Anyway, we passed by the amusement park, which was empty, slightly creepy and overgrown but still definitely running. To our left were various food stalls and Korean restaurants. To our right were long yards of parks, complete with statues dedicated to reunification. Straight ahead was the Peace Cable Car. The rest was steaming parking lot.

We headed to the cable car first, since that’s my friend’s FAVORITE thing ever. Seriously, I think she’s taken every cable car in Korea. We signed a security waver, showed our IDs, and paid 10,000 won (~$9) for a return trip. Then we boarded our glass-bottom cable car and passed over the Imjin River.

To our left was Freedom Bridge, a bridge used to repatriate POWs returned from North Korea. Now, obviously, it’s not used for anything but remembrance.

The cable car dropped us off on the other side, which was still technically South Korea but also now technically the DMZ. On this side lies Camp Greaves, an old US military base that’s been turned into an art enclave and hostel, as well as Daesong-Dong Village, the only civilian settlement in the DMZ. Really there wasn’t much to do except eat at their café or stand on the roof. Because of COVID, most of the area was closed off, including their bunker art installation.

Still, it was fascinating. There were signs marking mines every 5 ft or so, and barbed wired fences double-upped to make the walkable area very small.

After our return (we watched a car drive from a bridge across to the DMZ, a mystery), we plodded around some more. We ate sandwiches at the Dunkin Donuts and tried in vain to get coffee at the little café called 4B, but their espresso machine had broken and was being dissembled as we walked in.

The highlight of the visit was a quick look in their little museum, which offered some info about natural wildlife around the area and most interestingly, clips from the television show, Finding Dispersed Families.

This was a TV show that ran in the 80s in South Korea. It started as just a humble, one-off idea—let’s reunite a few families who were lost during the war—but it quickly grew so popular that the network ended up getting tens of thousands of calls, and reunited over 11,000 families.

There’s clips on youtube and I’ll warn you, it’s heartbreaking. Beautiful, but just so heartbreaking.

After, we braved the heat to walk up to the observatory. There, we used a 500 won coin to look through our telescopes at the North Korean mountains in the distance.

This was probably the most interesting part for me--seeing North Korea with my own eyes. I’d never want to visit for ethical reasons, but I confess it’s fascinating to me as it is for many foreigners.

We foreigners, Americans especially, have a unique fascination with North Korea. When I told my coteacher I wanted to visit, she was confused. She’d been forced to go as a field trip once and found it painfully boring.

Now, before I say what I’ll say next—obviously, my coteacher is just one person and her views don’t reflect the entirety or vastness of Korean opinions. There are still those who journey to Mangbaeddan memorial for Chuseok because they can’t return to the hometowns above the 38th parallel.

But for young Koreans, many feel the war was so long ago. The divided familial lines don’t cut as deep as they perhaps once did. In my coteacher’s views, North Koreans aren’t her brothers or sisters. They’re just other people. I find that most of my friends and many young Koreans I meet don’t think much at all about North Korea. If they do, it’s with disinterest. If it’s about reunification, it’s almost purely in economic terms.

Now Americans? We have almost this sacredness about the DMZ, no doubt because we have our own fascination with North Korea. I believe due to American propaganda and imperial interests, the media offers a confusing medley of contempt, sourness, and amusement—but also genuine concern about NK. I can’t tell you how many family members I had beg me not to go to Korea in 2018 because they were worried about missiles strikes from NK.

There’s this undercurrent belief that one day NK and SK will reunite; they are seen as the 21st century’s East and West Germany. In South Korea, reunification is a bipartisan ideal, one even taught in schools. Conservatives and progressives support it, they just differ on how. So it’s interesting how the status quo supports it, but the popular opinion is just a muddled bag of contention.

My coteacher theorizes in the future, the two countries will reunite—no, not because of lost loved ones, or decades of peace efforts, or the slow and enduring hand of democracy or anything like that, but because of population. SK’s birthrate is the lowest in the world—worse than Japan’s—and the government is has been sweating it for a while. They’re worried about the future of the Korean race. As an American, hearing “we’re worried about the extinction of our race” is a little funky to wrap my head around, but you gotta remember how the relationship between Korean nationality and ethnicity is very closely linked, near indistinguishable.

Rather than encouraging immigration or making it easier for young people to start families, my coteacher believes the Korean government will want the younger population of NK. After all, think of how much land there is to develop.

I sound quite cynical, and I’m not Korean so my understanding will always be surface-level. Still, I think going to the DMZ and having these discussions with my Korean friends has given me a much deeper understanding than I could have ever gotten from behind a keyboard or back in the US.

I recommend people to go…just maybe not for the tours to see North Korean villagers (that strikes me as morally indefensible). And I’ll never condemn someone for not wanting to visit the DMZ. If they’re not comfortable with that, I totally understand.

For me, going to the DMZ was an opportunity to learn, to reflect and to challenge my understanding of the war and of North Korea in South Korean society. Paju and Imjingak are a monument to a people’s pain but also their hope for their tenuous hope, even if it’s more complicated than it appears. I’m so grateful for this chance to remember and learn.

Thanks for reading.